‘Only some parts of these gigantic species will be seen, their remains will become garbage that the winds will scatter and will exist only in the human memory or in the descriptions of a genius.’ Lacépède.

After centuries of slaughtering, cetaceans find themselves in a fortunate situation. So, it is an honour to look back and recognize our companions from the early times of the SGHN as the seed of the sensitivity and study of Galician marine mammals. We would like to become a living part of those times in order to feel more intensely, if possible, the satisfaction of having contributed to ending industrial whaling in Galicia and in Spain. It goes without saying that we admire them and are proud of belonging to the same society.

Whaling is an activity known in our land since the 13th century, when traditional methods were used. In the 20th century, the whaling industry as such began with two companies founded in 1924, which closed at the end of the same decade. In the 1950s hunting of cetaceans reappeared in Galicia, the only place in Spain where it was practiced at that time. It started with two companies (Massó Hermanos and IBSA) and three land-based factories (Morás in Lugo, Caneliñas in Cee and Balea in Cangas), which were supplied by up to five whalers: Lobeiro, Carrumeiro, Ibsa I, Ibsa II and Ibsa III. The first four whalers were destroyed by explosives in an attack at the port of Marín.

In 1974, the Japanese multinational company Taiyo signed an agreement with the company IBSA to purchase their entire whale muscle mass, which belonged mainly to the Massó family of canners from Pontevedra and the lawyer and politician Iglesias Corral, which, for economic reasons, led to a considerable increase in the number of catches, including those of immature specimens, which were already in danger. IBSA hunted outside of international agreements, capturing protected species, without any form of supervision over this activity. Most of the catches were fin whales, sperm whales and even blue whales, which are on the brink of becoming an endangered species. Minimum catch sizes, number of catches, hunting of young whales or female whales with calves, legislative agreements (such as those of 1947 which allowed hunting only one whale per boat per day) were respected. Attempts to visit the factories, which were fully operational, have been hampered even by physical threats. Therefore, its activity had to be observed from the outside.

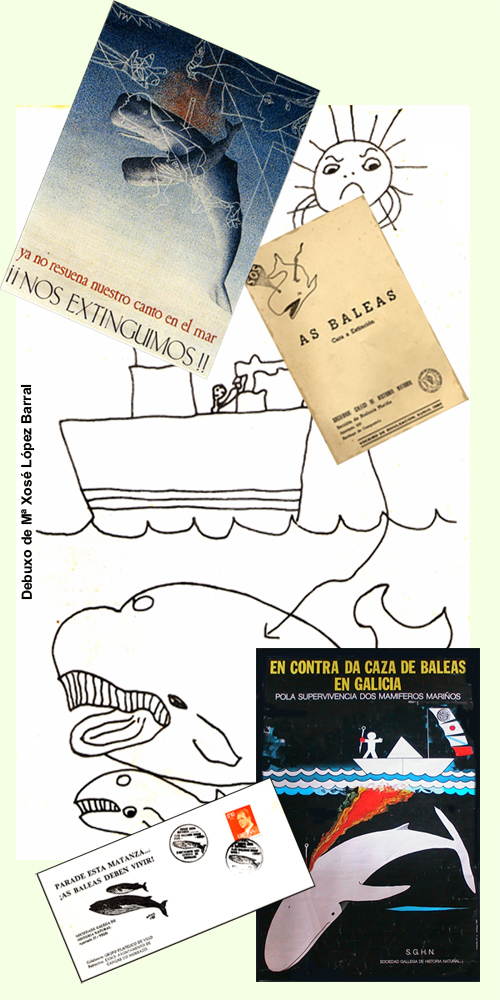

The population developed an increasing sense of rejection with regard to the extermination of whales as a symbol of the irrationality of an industry that seeks only profit. The raising awareness towards the environment and the living beings who surround us became reality in SGHN itself. A whose objective was to report information on the situation of cetaceans in Galician waters was established. Following the outcome, a campaign was launched in 1980 under the motto: ‘Stop whaling in Galicia. We want a law that protects marine mammals.’ This statement was widely accepted by the population which endorsed the request for a moratorium.

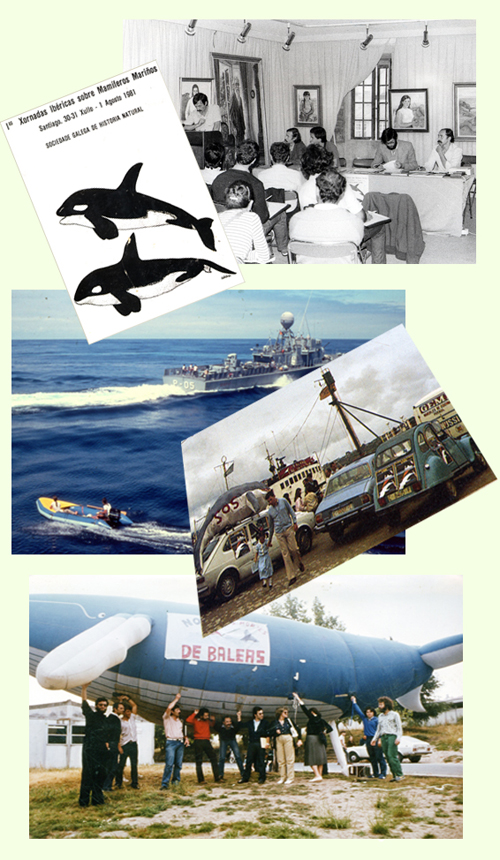

That same year, the Marine Biology Section of the SGHN published As baleas cara á extinción (Whales toward extinction) by Carlos Durán Neira, Xosé Manuel Penas Patiño and Antonio Piñeiro Seage. María Xosé López Barral’s drawings and Carlos Silvar’s posters illustrate the concern about a subject they sought to get across to the majority of the population. We marched in major towns of Galicia equipped with a PA system and carrying an inflatable whale, which represented those that SGHN desired to protect, calling for an indefinite moratorium on the hunting of marine mammals in Galician coastal waters and their protection, as stated in the General Environmental Law. Greenpeace which has been fighting whaling in Galicia since 1978, hinters whalers in open sea using small inflatable boats Their ship Rainbow Warrior was seized by the Spanish Navy and taken to the port of Ferrol, where its crew was held for five months, until the ecologist vessel managed to escape. The SGHN had some meetings with them (Remi Parmentier) in Coruña and Ferrol.

1980: En defensa dos mamíferos mariños

The campaign calling for the moratorium was supported by thousands and by many other associations across the Iberian Peninsula. As a result of all this interest in marine mammals, scientific studies interested in the bodies stranded on the beach were developed. Not only the respect and protection of cetaceans arose in 1980, but also the interest to broaden the knowledge of the hitherto unknown marine mammals and their biology. Studies about marine mammals were limited, difficult to find and old; it would be necessary to go back to the end of the 19th century (López Seoane and Graells) or the early 20th century (Cabrera). Hence the interest to have updated data and materials of their own. In order to exchange information, in the summer of 1981, the SGHN organized in Santiago the ‘1st Iberian Session about Marine Mammals.’ This led to the exchange of information and working methods in which, among other agreements, the need for a serious and continuous inspection of the factory by the Administration was established.

The SGHN, along with ASECA, AEPDEN, ADEGA, Amics de la Terra, Andalus, GEG, MEVO and Katagorri Taldea submitted a statement to the Subsecretariat of Fisheries signed by 120 000 people. We requested the immediate cessation of whaling activities, providing information of scientific nature and of the catches. Our petition reached every political party and resulted in the formulation of parliamentary questions. On 16th December, a bill adopted in February 1982 which forced the cessation of industrial activity in whaling was submitted. At the 34th meeting of the Commission, the Spanish delegation carried a position wanting to ban whaling to the CBI. This was decisive for the adoption of the international moratorium.

As Penas Patiño and Piñeiro Seage expressed in their book Cetáceos, focas e tartarugas mariñas das costas ibéricas (Cetaceans, seals and sea turtles of the Iberian coast):

‘The agreed moratorium represents an important victory for all environmental groups in Spain and for all those in the world who think that humans must know how to share the planet and rationally exploit its resources because the activities of the human species must never imply the extinction of any other living species.’

Text translated by Sergio Méndez Fernández (student of the Degree of Translation and Interpretation of the University of Vigo)